CARSTEN EGEVANG

About the Author

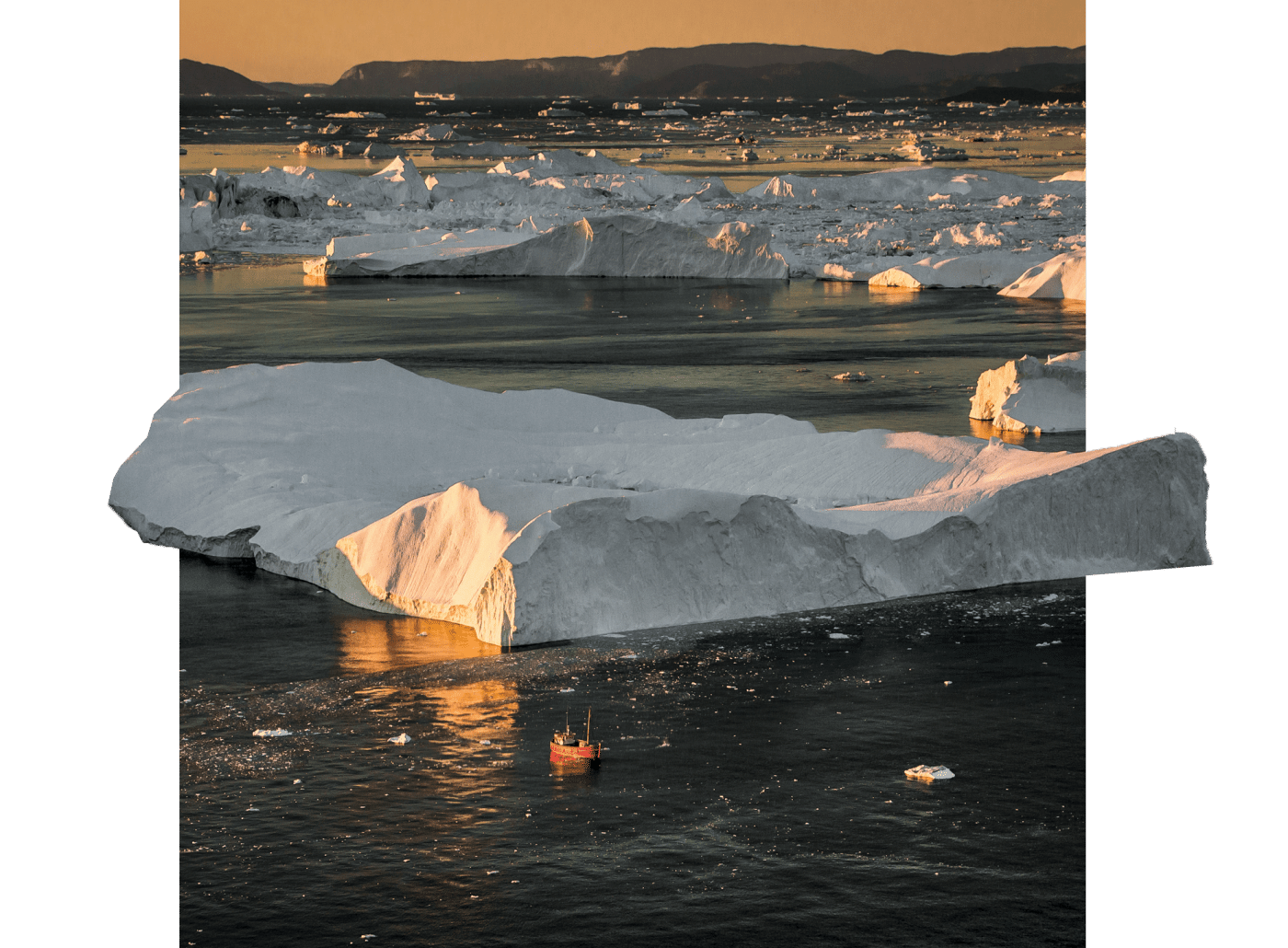

Carsten Egevang is a researcher of biology and an award-winning nature photographer, as well as the author of several books about Greenland. During the past 25 years, Carsten has traveled all over Greenland – even to the most remote areas – and always with binoculars and a camera around his neck. As a researcher at the Greenland Nature Institute in Nuuk, he has been responsible for the scientific work with seabirds in Greenland. Carsten’s Master’s degree (MSc) dealt with his favourite species of Greenlandic birds: the little auk. During his education as a researcher (PhD), he was the leader of a research group that was the first in the world to map the world’s longest bird migration: the Arctic tern’s incredible annual round trip from Greenland to Antarctica.

Today, Carsten works mainly as a photographer, where he combines his scientific background with visual communication. The unique relationship between prey animals and traditional Greenlandic hunting culture is the particular focus of his professional work. Most recently, he has worked with the Greenlandic sled dog, and its significance in Greenland today.

Birdwatching

There are a number of common features that characterise bird life in Greenland: