A short history

of music in Greenland

The musical history of Greenland begins long before anyone can remember – long before anyone wrote anything down in the Arctic regions, and at a time of which archeology and legends are our only source of knowledge. Back then, life played out in a constant interaction (and sometimes struggle) between man, their prey, and the elements. It may come as a surprise that those who inhabited Greenland over 4,000 years ago had time for music, but when stomachs were full and people crouched together on the benches inside skin tents or turf houses, the drum, qilaat, was brought out and used for a mixture of dance, song, storytelling and music. This drum technique is used in various variations from Siberia to Greenland and remains a living tradition to this day.

There is no evidence that the Norsemen, a Viking people who inhabited Greenland from the late 900s to the mid-15th century, introduced any lasting music culture to Greenland, but when Europeans once again began to navigate the waters around Greenland, primarily to catch whales, they brought with them contemporary folk culture in the form of music and dance. The whalers eagerly traded with the Inuit, and in this context music was played for dancing on whatever instruments were available. In this way, the Greenlanders learned the European repertoire, which was transformed into the tradition kalattuut, which resembles other folk music and dance traditions in the North Atlantic but is characterised by being faster. If you are going to a party in Greenland, you must therefore have chalked up your dancing shoes, because you may be lucky enough to be invited to a Greenlandic polka. And this does not go over quietly.

When Denmark began the colonisation of West Greenland in 1721, drum song and drum dancing were pushed into the background and choir and hymn singing were introduced. The German Moravian missionaries, in particular, understood how to use music for preaching, and had a great impact on the Greenlandic choir tradition. Over time, Greenlandic intellectuals began to compose choral music which has its very own singing style and is famous across the world.

The Danish state introduced a strict colonisation policy in Greenland until World War II, during which Greenland was kept relatively isolated from the rest of the world, although modernisation did take place, especially in West Greenland. But Greenlanders did not have free access to Western culture until Nazi Germany occupied Denmark in 1940, and they began cooperating with the Americans regarding the protection of and supply to the country. World War II thus became a cultural injection for Greenlanders, and when the war was over, Greenlanders wanted the opening of the country to continue. As a result, Greenland’s colonial status ceased in 1953, and the country became a nation within the Kingdom of Denmark. In the years that followed, a Greenlandic country and western genre, called Vaigat music, emerged in the mining town of Qullissat in Disko Bay, and in the 1960s the first Greenlandic rock’n’roll bands began to play international hits in bars and community centres, especially in the capital city of Nuuk.

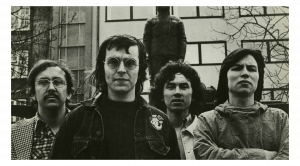

The 1970s saw a revolution in Greenlandic music, in the form of the band Sumé, which was made up of Greenlandic students in Copenhagen. The group wrote rock music in Greenlandic, about Greenlandic topics and using Inuit symbols. Thus, the group’s music crystallized an increasing desire for a Greenland ruled by Greenlanders and rooted in Greenlandic culture, and this desire led to the introduction of Home Rule in Greenland in 1979.

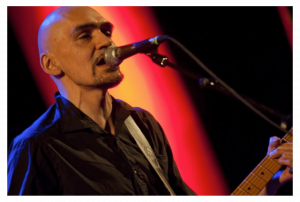

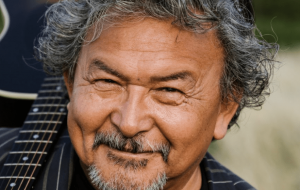

Since Sumé, Greenlandic music has moved in many different directions, but there is still widespread use of the Greenlandic language, national themes and Inuit symbolism, whether the genre is rock, rap or heavy metal. Some artists have succeeded in creating an audience outside Greenland, but the Greenlandic music scene is characterised to a very large extent by its reference to a Greenlandic audience, and is a unifying element for a small population who live scattered across enormous distances on the world’s largest island.