What’s the difference between calving and a GLOF outburst?

Calving is the detachment/break-off of ice from a glacier, forming icebergs. A GLOF is a sudden outburst of water from beneath or adjacent to a glacier.

The towering ice cliff of Russell Glacier is a popular attraction in Kangerlussuaq, located just 25 km away from the settlement, and a fantastic and accessible part of the ice sheet to visit on your travels through the gateway to Greenland.

Russell Glacier is well studied by scientists, in part due to its easy access. The majority of the front of Russell Glacier terminates on land, ending in an impressive ice cliff that is approximately 60 metres tall. Melt from the glacier drains away, forming a large river and delta system downstream called Akuliarusiarsuup Kuua, or the Watson River.

Water also pools in front of the northern sector of the glacier front, forming a lake. This lake is special in its dynamics, as it is dammed by the ice adjacent to it and can spontaneously burst and cause catastrophic flooding. Such flood events are often referred to as GLOFs (Glacial Lake Outburst Floods), or by their Icelandic name, jökulhlaup, which translates as ‘glacier run’.

These special types of lakes are called ice-marginal lakes, and feature in front of glaciers all across the world, including Iceland, the Himalayas, Alaska, and Greenland. My work has focused on ice-marginal lakes in Greenland, where our recent study suggests that there could be over 3000 ice-marginal lakes in Greenland. The lake in front of Russell Glacier is likely one of the most well-studied ice-marginal lakes in the world.

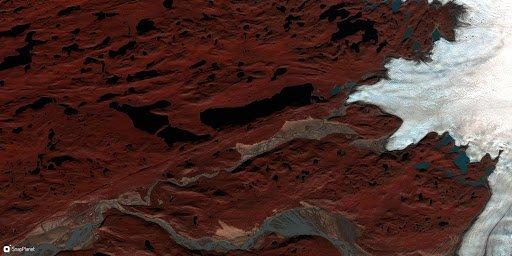

A false colour satellite image of the Kangerlussuaq area, including the settlement and glacial river flowing into it, along with Russell Glacier and its ice-marginal lake

Records of jökulhlaups from Russell Glacier have been dated back to at least the 1940s through aerial photographs, downstream discharge and sediment records, time-lapse cameras, and direct observations. Jökulhlaups occurred at Russell Glacier every two or three years up until 1987, following which there was a long dormant period of 20 years where no jökulhlaups were recorded.

In 2007, the largest jökulhlaup on record at Russell Glacier occurred where approximately 39.1 million m3 of water was released over the course of 17 hours. This equates to over 15,000 Olympic swimming pools, with outflow discharge averaging at around a quarter of an Olympic swimming pool per second. Since 2007, jökulhlaups have been occurring at Russell Glacier nearly on a near-annual basis, usually in the summer season between June and September.

So, a key question that scientists have tried to answer is why did the frequency of jökulhlaups change at Russell Glacier? Theoretically, jökulhlaups cycles are shaped by the changing conditions of the glacier, such as glacier position and the thickness of the ice, which also alters the position and strength of the lake dam.

The 2019 partial drainage of Russell Glacier’s ice-marginal lake, captured from sequential false colour satellite images

Russell Glacier has been through various advance and retreat phases in its lifetime. A notable advance-retreat phase was a period of advance between 1987 and 1999, followed immediately by a recession of approximately 50 m and drastic ice thinning, with the ice surface lowering by around 10 m. The glacier’s advance coincided with the 20-year dormant phase in jökulhlaups, and it is likely that the following retreat phase triggered the new wave of jökulhlaups.

Scientists continue to study Russell Glacier and its ice-marginal lake to better understand its dynamics and how it will change in the future. It is hoped that by gaining further insight here, this will unlock the ways in which these processes operate at other glaciers, perhaps even on a global scale. There is a long way to go to reach this point, with several untapped avenues for scientists to explore. One of these includes the incorporation of Greenlandic knowledge and observations, as our understanding thus far has been based on few, if any, insights from locals which would be an incredibly valuable and powerful record if fully and properly utilised.

Architecture in Greenland

Scroll to top

Architecture in Greenland

Scroll to top